Maternal health equity and infant health injustices

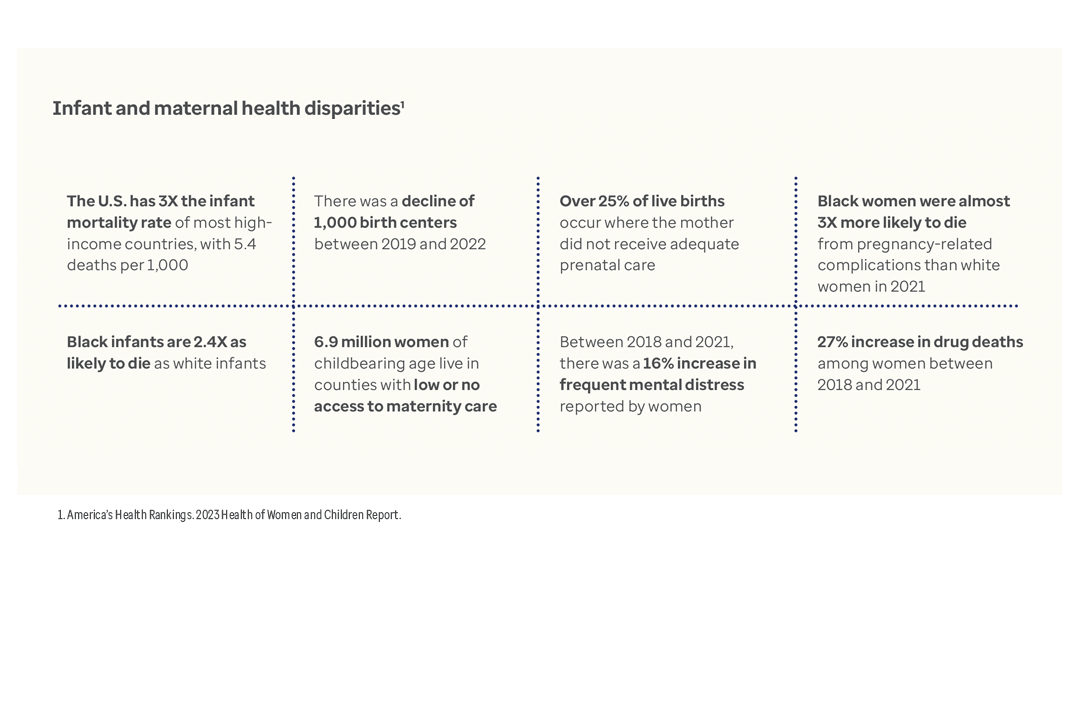

Across the country, women face rising maternal mortality and morbidity rates, as well as declining access to services. For infants, the U.S. mortality rate is 3 times greater than most high-income countries.¹

The root causes of these alarming trends are tied to poverty and limited access to prenatal and primary care. The following case studies outline how the state of Indiana and the District of Columbia are tackling this mounting health crisis.