Orphan drugs are treatments aimed at very small patient populations, usually with no other treatment options available. Orphan drugs also have a special regulatory status that confers government financial incentives. These incentives are designed to promote drug development for conditions too rare to generate the profits needed to offset their costs.1

Orphan drugs can provide a drastic improvement in the lives of people with rare diseases. But orphan prices are high — some of the most expensive on the market.2

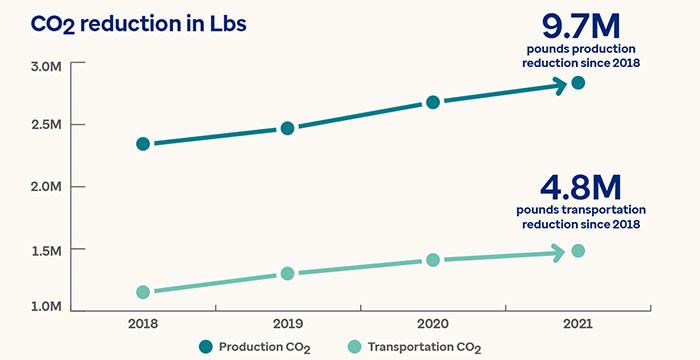

The chart below highlights the wide disparity in costs for orphan versus non-orphan drugs. It shows median wholesale acquisition costs (WAC) for a new drug upon U.S. market entry (2021 dollars). Note the red circles. They indicate that only 7 non-orphan drugs exceeded the median cost of orphan treatment (~$219K/treatment). Instead, non-orphan drugs tend to cluster toward the bottom of the scale.

Orphan drug prices significantly higher at launch

This graph shows wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) prices for orphan and non-orphan drugs at launch for the years 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020 and 2021. The median WAC for orphan drugs is $218, 872, while the median price for non-orphan drugs is $12,798. Only 7 non-orphan drugs launched with prices higher than the median for orphan drugs during this period.

Notably, costs rise substantially when drugs originally intended for a few thousand patients start to be used for much more common conditions.3 As a result, plan sponsors are increasingly struggling to fund them.4

Optum Rx is closely tracking this situation, and we have deployed multiple solutions that are helping our clients meet this challenge head-on. In this article we will examine some of the key questions around orphan drugs:

Why are orphan drugs so expensive?

In 1994, one of the pioneering biotechnology firms (then called Genzyme), launched a new enzyme replacement therapy called Cerezyme® (imiglucerase). Intended to treat Gaucher’s disease, a rare genetic disorder, Cerezyme was by no means the first orphan drug. What made it notable was the price. In the U.S., Cerezyme was priced at ~$200,000 per year for an average patient.5

This was a high price at the time. Historical data show that Cerezyme’s launch price was more than 2,400% higher than the mean cost for new chronic medications for the same period ($825 per year).6

In effect, Genzyme had just invented the high-price rare disease business model. They realized that if the industry was ever going to consistently develop drugs for very rare conditions, they had to be priced to make it a financially sustainable business. And the only way to do that was to charge a high price.7

This pricing strategy assumed that, since Cerezyme and other orphan drugs affected so few patients, the healthcare system could absorb the high prices with relative ease. In the process, a severely underserved population could get urgently needed care.8

Where are we now?

Today, the majority of all novel drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are orphan drugs. More than half of all novel drugs approved by the FDA had orphan designations in 2020, 2021 and 2022.11, 12

High prices are certainly not limited to orphan drugs. But there is an unmistakable trend toward higher prices for orphan drugs.13

- Of the orphan drugs available, 39% cost more than $100,000 annually.14

- The newly available gene and cell therapies can cost anywhere from $1–$3 million dollars.15

- Among the 100 best-selling drugs in the U.S., the average cost of treatment for orphan drugs is 4.5 times that of non-orphan drugs ($150,854 vs. $33,654 per year).16

This graph shows the increasing revenue from orphan drugs over the last decade. More important, it shows that the number of orphan drugs — and spending — are projected to grow rapidly in the very near future.

Spending for orphan drugs will keep accelerating

This graph shows revenue from orphan drug sales from 2012 and projected through 2026. Spending grew by $89 billion in the 10 years from 2012–2021, but is expected to grow by $100 billion in the next 5 years (2022–2026).

Are orphan drugs still being used primarily for rare diseases?

Not all orphan drug utilization is for orphan conditions. Some drugs that receive approval for orphan disease indications may also receive approval to treat more common diseases.

Here are a few examples of top-selling drugs that have both orphan and non-orphan indications:

- Humira® (adalimumab): Non-orphan approval in 2002; orphan approval added in 2008. 6 non-orphan indications and 7 orphan indications. Nearly 85% of spending was for non-orphan indications in 2018.17

- Remicade® (infiximab): Orphan approval in 1998; non-orphan use added in 1999. 5 non-orphan indications and 3 orphan indications. Approximately 54% of 2018 spend assigned to orphan indications, 37.8% to non-orphan indications.18

- Enbrel® (etanercept): Non-orphan approval in 1998; orphan status added in 1999. 4 non-orphan designations and 1 orphan designation. Nearly 94% of its spending is for non-orphan indications.19

Building on these examples, this graph shows two important things:

- Orphan drugs now constitute nearly one third (27%) of the $518 billion in U.S. drug expenditure.

- For drugs with both orphan and non-orphan indications, spending for non-orphan indications ($83 billion) was 46% higher than for orphan indications ($57 billion).

This chart shows total U.S. drug spend ($518 billion) plus spending for orphan drugs.

This chart shows total U.S. drug spend ($518 billion) plus spending for orphan drugs. The total spend for orphan drugs is $140 billion (27% of the total). But just 11% ($57 billion) of orphan drug spending is for orphan conditions. 16% of spending for orphan drugs is for non-orphan indications ($83 billion).

Rise of the partial orphans

Orphan drugs approved to treat both rare and common diseases are called partial orphans.20

Partial orphan drugs are drawing increasing scrutiny. The basic question is whether the incentives designed to accelerate rare disease drug development are appropriate for drugs used more widely.21

A recent study found that of the 15 top-selling partial orphan drugs in 2018, just 21% of the total dollars spent went to treat a rare disease. Meanwhile, more than 70% went to treat common diseases. (The balance, about 8% of spend, did not fall in either category, indicating off-label use.)22

One orphan-designated chemotherapy support drug, Neulasta® (pegfilgrastim), was called out specifically: Only 0.6% of Neulasta spending went to its rare disease role.23

The increased use of orphan drugs for non-orphan indications creates at least two potential problems:

- The FDA recognizes the difficulties presented by such small numbers of patients. For example, it’s very difficult to recruit enough patients for a typical randomized study. As a result, orphan drugs can be approved based on smaller trials with less evidence.24

Small trials may be sufficient for rare conditions, but they’re not ideal when it comes to evaluating their use in significantly larger populations.25 - As we’ve seen, orphan drugs are usually launched with disproportionately higher prices compared to other drugs. However, these prices almost never come down once they are approved for more common conditions.26

Big future for orphan drugs

The high prices commanded by orphan drugs often mean they are much more profitable to produce than non-orphan drugs.27 Consequently, the stage is set for many more orphan drugs in the future:

- Overall, 40% of all new medicines now in development are orphan drugs. These include approximately 179 ongoing trials for gene therapies that target rare diseases.28

- Worldwide, orphan drug sales are forecast to grow nearly twice as fast as projected for the non-orphan drug market.29

Circling back to Genzyme, the high-cost strategy they crafted for a specific time and circumstance has now become ubiquitous. In the process, high-cost orphan drugs have become one of the biggest challenges facing drug makers, payers and patients alike.30

Can the employer insurance payment model cope with this situation?

Healthcare payers are challenged in balancing affordability and patient access to this growing wave of high-cost therapies. The trouble is, there are just not that many plan design levers to pull to come up with an extra $2 or $3 million dollars for a single orphan disease treatment.

Instead, plan sponsors are using customary management tools like prior authorization, step therapy and quantity limits to help control costs.31

Changes slow in coming

While the problem of rising drug costs is clear, there have not been any significant changes in the basic drug pricing mechanisms in the U.S.32 While the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 does signal some change, it is only aimed at Federal programs like Medicare and Medicaid.33

Which doesn’t mean that nothing can ever change. Bipartisan public sentiment — including stakeholders like payers and employers — may be leaning toward future market interventions.34

One proposed intervention would address the profits drug makers can reap when high-cost orphan drugs are also used for common conditions. Current law prohibits competition for new orphan drugs for seven years. The proposed change would revoke exclusivity once a drug proved to be profitable with larger sales.35

What should plan sponsors do next?

While policymakers debate how or whether to adjust the Orphan Drug Act, plan sponsors are wondering what to do next. Optum Rx has designed an array of plan design tools that can help plan sponsors manage orphan drug costs as closely as possible. Here is a brief run-down on 3 of them:

Optum Rx® Orphan Drug program

The Optum Rx Orphan Drug program deploys specialized pharmacists who deliver advanced clinical counseling for members who take certain high-impact orphan drugs. They can help determine which drugs are working, and which aren’t.

As a result, your members can see optimal health outcomes, while you stop paying for ineffective drugs.

Clients using the Orphan Drug program save an average of $147,000 per drug discontinuation.36

Optum Rx® Specialty Standards

The new Optum Rx Specialty Standards program takes traditional management strategies to a new level by focusing on orphan and rare disease therapies.

- Expert specialty clinicians apply extra scrutiny to make sure that members get the right dose at the right time for the right price.

- Sophisticated new adjudication technology monitors and adjusts refill behaviors and package sizes.

- A new non-preferred specialty tier formulary option encourages members to use preferred and clinically appropriate medications.

Specialty Standards can help improve outcomes and drive down specialty benefit costs for years to come. Participating clients see average savings of $1.50 per member per month.37

Optum Rx® Review My Care program

Specialty drug patients may experience changes in their condition. Or, a new medication arrives, or clinical treatment guidelines are updated. In fact, almost half of all specialty therapies present an opportunity to stop or adjust therapy within 18 months of prior authorization.

The Optum Rx Review My Care program helps align our clinical experts with prescribers. Together, the goal is to identify opportunities to change treatment to improve member outcomes and specialty trend management.

In one documented case, changing just one medication for one person resulted in pharmacy savings of $232,800 per year.38

In summary

It is clear that there will be no simple, single answer to the broad and complex problem of orphan drug costs. But Optum Rx is ready to work with you in order to take advantage of some of these extraordinary health advances — in a science-driven way that manages toward everyone’s best interests.

Please contact your consultant, broker or Optum Rx representative for more about how Optum Rx can help you manage the orphan drug phenomenon.

Related healthcare insights

Article

Prices for popular brand-name biologics drop up to 60% with generic-equivalent biosimilars.

Guide

Read the most recent quarterly reports on new drugs coming down the pipeline.

In this conversation, discover how new weight loss drugs like Wegovy are changing obesity management and their connection to diabetes.